Charles Richard Drew, MD (1904–1950)

Known as the “father of blood banking,” Charles Richard Drew, MD, pioneered blood preservation techniques that led to thousands of lifesaving blood donations. Drew’s doctoral research explored best practices for banking and transfusions, and its insights helped him establish the first large-scale blood banks. Drew directed the Blood for Britain project, which shipped much-needed plasma to England during World War II. Drew then led the first American Red Cross Blood Bank and created mobile blood donation stations that are now known as bloodmobiles. But Drew’s work was not without struggle. He protested the American Red Cross’ policy of segregating blood by race and ultimately resigned from the organization.

Despite his renown for blood preservation, Drew’s true passion was surgery. He was appointed chairman of the Department of Surgery and Chief of Surgery at Freedmen’s Hospital (now known as Howard University Hospital) in Washington, D.C. He also became the first African American to be appointed an examiner for the American Board of Surgery. Throughout his life, Drew went to great lengths to support young African Americans pursuing careers in the medical discipline.

Drew’s innovative work was recognized by awards and honors including the 1942 E.S. Jones Award for Research in Medical Science from the John A. Andrew Clinic in Tuskegee, AL; an appointment to the American-Soviet Committee on Science in 1943; the 1944 Spingarn Medal from the NAACP for his work on blood and plasma; honorary doctorates from Virginia State College (1945) and Amherst College (1947); and election to the International College of Surgeons in 1946.

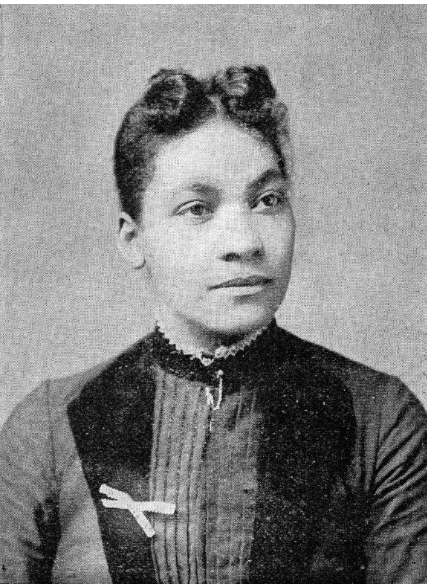

Jane Cooke Wright, MD (1919–2013)

The daughter of one of the first Black American graduates of Harvard Medical School, Jane Cooke Wright grew up with an avid interest in healthcare. Her father, Dr. Louis Wright, was also the first Black doctor appointed to a staff position at a municipal hospital in New York City, and in 1929, the city hired him as police surgeon—the first African American to hold that position.

After earning her medical degree, Dr. Jane Cooke Wright worked alongside her father at the Cancer Research Foundation in Harlem, which her father established in 1948. Together, father and daughter researched chemotherapy drugs that led to remissions in patients with leukemia and lymphoma.

In 1952, when her father died of tuberculosis, Wright became the head of the Cancer Research Foundation at age 33. She created an innovative technique to test the effect of drugs on cancer cells by using patient tissue rather than laboratory mice. She advanced to work as the director of cancer chemotherapy at New York University Medical Center, and she was an associate dean at New York Medical College.

The New York Cancer Society elected Wright as its first woman president in 1971. Her research helped transform chemotherapy from a last resort to a viable treatment for cancer.

Otis F. Boykin (1920–1982)

Born in Dallas, Texas in 1920, Otis Boykin hurdled many obstacles to pursue his life’s calling—inventing electronic innovations.

Born in Dallas, Texas in 1920, Otis Boykin hurdled many obstacles to pursue his life’s calling—inventing electronic innovations.

During his career, Boykin patented 28 electronic devices. His many inventions included a chemical air filter, a burglarproof cash register, and various resistors for electronic components that made the production of televisions and computers more affordable. His most famous invention, however, was a control unit for the cardiac pacemaker, which used electrical impulses to stimulate the heart and create a steady heartbeat.

In a tragic twist of fate, Boykin died in 1982 as a result of heart failure. The long-lasting effects of his pioneering ingenuity are still felt today in the medical world and beyond.

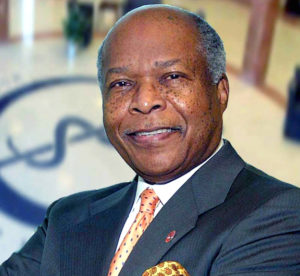

Louis Wade Sullivan, MD (b. 1933)

Louis Wade Sullivan, MD, grew up in the racially segregated rural South in the 1930s. There, he was inspired by his doctor, Joseph Griffin. “He was the only Black physician in a radius of 100 miles,” Sullivan said. “I saw that Dr. Griffin was really doing something important and he was highly respected in the community.”

Louis Wade Sullivan, MD, grew up in the racially segregated rural South in the 1930s. There, he was inspired by his doctor, Joseph Griffin. “He was the only Black physician in a radius of 100 miles,” Sullivan said. “I saw that Dr. Griffin was really doing something important and he was highly respected in the community.”

Over the decades, Sullivan became an equally profound source of inspiration. The only Black student in his class at Boston University School of Medicine, he would later serve on the faculty from 1966 to 1975. In 1975, he became the founding dean of what became the Morehouse School of Medicine—the first predominantly Black medical school opened in the United States in the 20th century. Later, Sullivan was tapped to serve as secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, where he directed the creation of the Office of Minority Programs in the National Institutes of Health’s Office of the Director.

Sullivan has chaired numerous influential groups and institutions, from the President’s Advisory Council on Historically Black Colleges and Universities to the National Health Museum. He is CEO and chair of the Sullivan Alliance, an organization he created in 2005 to increase racial and ethnic minority representation in health care.

Marilyn Hughes Gaston, MD (b. 1939)

In a pivotal experience while working as an intern at Philadelphia General Hospital in 1964, Marilyn Hughes Gaston, MD, admitted a baby with a swollen, infected hand. The baby suffered from sickle cell disease, which hadn’t occurred to Gaston until her supervisor suggested the possibility. Gaston quickly committed herself to learning more about it, and eventually became a leading researcher on the disease, which affects millions of people around the world. She became a deputy branch chief of the Sickle Cell Disease Branch at the National Institutes of Health, and her groundbreaking 1986 study led to a national sickle cell disease screening program for newborns. Her research showed both the benefits of screening for sickle cell disease at birth and the effectiveness of penicillin to prevent infection from sepsis, which can be fatal in children with the disease.

In a pivotal experience while working as an intern at Philadelphia General Hospital in 1964, Marilyn Hughes Gaston, MD, admitted a baby with a swollen, infected hand. The baby suffered from sickle cell disease, which hadn’t occurred to Gaston until her supervisor suggested the possibility. Gaston quickly committed herself to learning more about it, and eventually became a leading researcher on the disease, which affects millions of people around the world. She became a deputy branch chief of the Sickle Cell Disease Branch at the National Institutes of Health, and her groundbreaking 1986 study led to a national sickle cell disease screening program for newborns. Her research showed both the benefits of screening for sickle cell disease at birth and the effectiveness of penicillin to prevent infection from sepsis, which can be fatal in children with the disease.

In 1990, Gaston became the first Black female physician to be appointed director of the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Bureau of Primary Health Care. She was also the second Black woman to serve as assistant surgeon general as well as achieve the rank of rear admiral in the U.S. Public Health Service. Gaston has been honored with every award that the Public Health Service bestows.